This trip was taken in February of 2019.

Like a festering wound, the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) cuts through the Korean peninsula.

Established in the aftermath of the Korean War (1950-53) along ideological lines, this 250-kilometre-long strip of land roughly follows the 38th parallel and splits a once united nation in half.

Since the end of the conflict, numerous efforts have been undertaken to seal it, yet every time tensions between these two brother nations seem to ebb away, it gets ripped open again, disrupting the healing process.

Taunting both sides, it is the symptom of this ongoing conflict, serving as a constant reminder that the two Koreas are officially still in a state of war.

When North Korean soldiers crossed the 38th parallel in June 1950, no one could have predicted that these actions would kickstart a war that never ended, a war that, nearly 70 years after the last major combat operation, is still seeking a resolution.

The morning sky is shrouded in clouds, as we depart for the DMZ.

Driving along the Taedong-gang River, which meanders through the North Korean capital, we pass inornate apartment blocks and smoke belching factories, the tranquillity of the morning only disrupted by the scraping noise of huge machinery dredging the riverbed of sediments.

Following the Reunification Highway, the first sunrays, promising a beautiful winter day, reveal an impressive sight.

Looming in front of us are two women in traditional Korean dresses, reaching across the road. In their palms they hold a sphere, showing an undivided Korean peninsula.

The sphere is representing the Three Charters: The Three Principles of National Reunification, the Plan of Establishing the Democratic Federal Republic of Korea, and the Ten Point Program of the Great Unity of the Whole Nation.

The 30-meter-high and over 60-meter-wide Arch of Reunification, spanning the entirety of the highway, was constructed in 2001 to commemorate the (albeit unsuccessful) efforts, made by North Korea’s first leader Kim Il-sung, to reunite the Korean people under one flag once again.

In his writings, Kim Il-sung called for a unified and peaceful process, independent from foreign interference, shaping North Korea’s view on the matter. Despite the aggressive tone of his grandson and current leader of the DPRK, Kim Jong-un, his ideas are still the driving force behind the North’s policy towards reunification.

However, the arch is as much a sign of hope for a united future, as it is a dream of the past.

A Korean federacy (a communist North coexisting with a capitalist South), is nothing but a pipe dream of the North, and, although worth striving for, strikes me as wishful thinking rather than anything else.

Leaving Pyongyang behind us, we pass picturesque villages doting the brown and undulating countryside, the farmhouses covered by traditional Korean roofing. The snow is glistening in the rays of the morning sun, bathing the rugged, yet simultaneously beautiful landscape in warm light.

I catch sight of people in the fields, some on foot, some on their bikes. There is even a man trying to hitch a hike. I wonder if he’ll be successful, considering the non-existent traffic.

The road, connecting the capital Pyongyang with Kaesong in the southern part of the country, is the only major highway in the DPRK, yet it is eerily empty. Private cars are still a luxury in North Korea and travel within the country is tightly regulated by the ruling party. The road conditions play their part, as well. Cracks and potholes riddle the tarmac, a striking contrast to the modern infrastructure found in the South.

We stop for a few minutes, giving me the opportunity to question our Korean guides Jo and Chang about their view on the ongoing conflict with South Korea.

Before coming to the DPRK I wasn’t sure how much our guides would or could talk about sensitive issues like this. Surprisingly, they not only share their thoughts with us, but seem more than happy to give their view on the matter.

After all the bloodshed, they hold no grudge against their southern neighbour. In their understanding, unfortunate circumstances and the interference of outside, imperialist powers led to war and the division of the peninsula, an outcome not wanted by the Korean people.

In the eyes of the North Koreans, the attack on the South was not an act of aggression, as much as it was a response to the occupation of the southern part of the peninsula by American forces. To this day they refer to the Korean War as the “Fatherland Liberation War” in the DPRK.

This narrative greatly contradicts the Western perspective that condemns the North Korean instigators.

Sharing their dream of peaceful reunification with their lost brothers and sisters, I am eager to know if they still have family in the South. They deny. Maybe some distant cousins or the sorts, however they wouldn’t know each other. Too much time has passed since one country became two.

Standing in an empty parking lot somewhere in North Korea, I begin to wonder if reunification is even possible, come the day the last family ties sever.

What will be left to bind North and South together?

After two and a half hours we reach Kaesong, the former capital of the kingdom of Goryeo (roughly 918-1392 A.D.), from which most western languages derivate the modern name Korea.

The city sits right at the border with South Korea and is just a short ride away from the Joint Security Area in Panmunjom, today’s destination.

As I step off the bus at the DMZ visitor centre, my attention gets caught by two murals.

Once again, they depict slogans and imagery calling for a pacific solution to the inner-Korean conflict.

However, this apparent desire for a peaceful resolving of the conflict doesn’t seem to fit the rhetorical sabre-rattling, the massive show of military force and the regular nuclear weapon tests, being undertaken by the North Korean leadership.

Is this just another puzzle piece in their propaganda strategy aiming to deceive Western tourists and mask the country’s real intentions?

Or are the remarks made by our guides and those pleas written in stone the expression of a genuine, deep-rooted hope for a future, in which the wounds of the past can finally heal?

Is it too farfetched to imagine a people wishing to reunite with their former kinsmen and to end a war that started all those decades ago?

After getting a short overview of today’s tour, we hop back on the bus and enter the DMZ.

The road, just wide enough for a single vehicle to pass at a time, cuts through an earth wall. Held by thick steel cables, giant boulders rest on both sides, ready to be cut loose and block the passage in case of an attack.

Heading deeper into no-man’s-land, I remind myself where I am.

This is not your ordinary Sunday trip.

Even though, this roughly four-kilometre-wide strip of land, nestled in between these two hostile nations, provides a living environment to a couple of farming communities (yes, there are actually people living inside the DMZ!), the borders themselves are anything but demilitarized.

Hundreds of kilometres of trenches, barbed wire, fences, guard towers and gun emplacements, as well as, what is believed to be hundreds of thousands of landmines surround the state lines, making it one of the most heavily fortified places on earth.

An invasion effort, conducted by either side, would be outright foolish, and although, the 38th parallel hasn’t seen any major battles since the armistice in 1953, there have been numerous minor incidents, most notably the discovery of a couple of North Korean invasion tunnels (detected between 1974 and 1990).

Historically, South Korean propaganda actions and smaller skirmishes inside the DMZ have not been a rarity either, but have decreased in the last years, due to intensified diplomatic efforts.

However, the North Korean border fulfils a completely different function, as well. It serves as a deterrent for potential defectors trying to flee the North. Despite the danger of such an endeavour, now and then a daredevil escape attempt catches the attention of Western media, enforcing the believe of disastrous conditions in the DPRK.

Moving through the no-man’s land, two giant flagpoles, one on each side, indicate that we find ourselves between the fronts now.

Our first stop is a cluster of buildings, surrounded by a well-kept garden. Pines and neatly trimmed box trees line the asphalted pathway. The houses are designed in the traditional Korean style and, apart from the dark brown wooden beams holding the roof, completely painted in white.

The colour choice is no coincidence. We are standing in front of the very same huts, inside which delegates of North and South Korea, as well as the United States, were debating a ceasefire on the Korean peninsula.

The first building is small and austere. A couple of green lamps with white shades hang above wooden tables. Windows and doors are framed in blue. There is no pomp, no grand halls, no lavishly furnished rooms. This is as utilitarian as it gets, its only purpose to provide a place to conclude peace.

The second hut boasts a peace dove above its entrance. This is where the armistice was finally signed on 27 July 1953. Pictures of the negotiations decorate the walls.

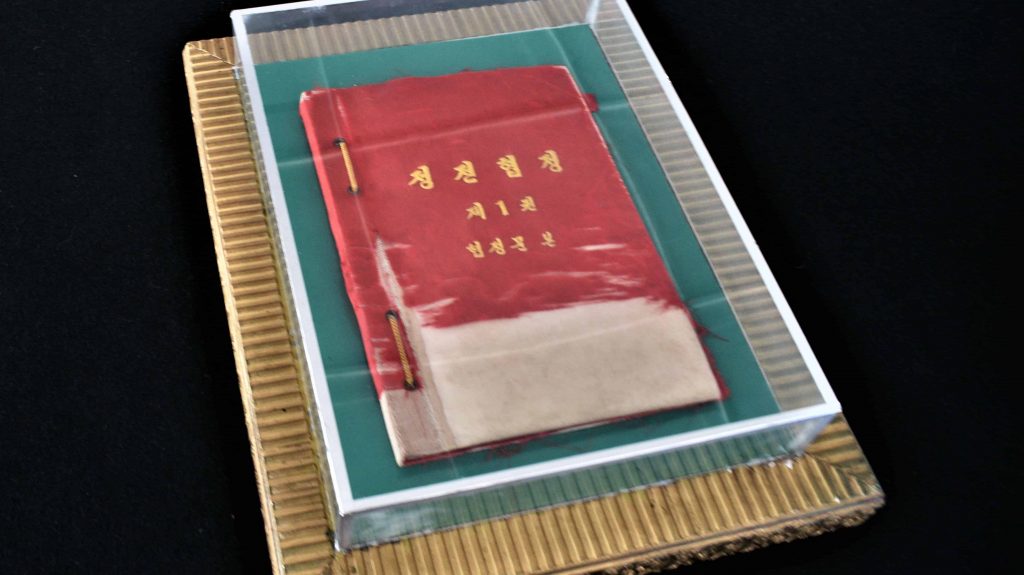

An insignificant looking red booklet, covered by a glass showcase, lies on one of the tables. Yellow characters embellish its front. It is showing its age, the front cover fizzling out at the bottom.

Despite its unremarkable appearance, the document is the reason the DMZ even exists in the first place.

This is the original ceasefire agreement, written and signed in 1953.

Soon after, we step onto the balcony of the Panmun Pavilion, offering a great view of the Joint Security Area of Panmunjom below.

Across the Military Demarcation Line (MDL), lies the Freedom House, its glass façade reflecting the world-famous blue barracks.

On one side an economic miracle, on the other a nation held back by a failed system not competitive in our modern world.

This is the heart of the DMZ.

It was here, in 2018, that South Korean president Moon Jae-in invited Kim Jong-un to cross the MDL, making him the first North Korean leader to set foot on South Korean soil since the end of the Korean war.

A year later, on 30 June 2019, Donald Trump became the first U.S. president in office to take a step into North Korea.

After years of uncertainty, the world observed the Korean peninsula with confidence rather than apprehension. It seemed like a new age was dawning for the Korean people and hopes arose that this decade old conflict would finally come to an end.

Yet, after all these promising steps towards a peaceful resolution, what stays is disillusionment.

North Korea has resumed its nuclear weapon tests and aggressive rhetoric, while the United States’ focus appears to have shifted from the DPRK to more urgent matters at home and in other parts of the world.

Additionally, in June 2020, as a response to a South Korean propaganda action, the North Korean leadership ordered the joint liaison office with South Korea (only installed in 2018) to be detonated, dealing yet another blow to the inner-Korean relationships and stoking concerns of further escalation of the conflict.

Most of these things have not happened yet of course.

On this sunny day in February 2019, relations between the DPRK and South Korea are on a high and tensions low. Donald Trump is preparing to meet Kim Jong-un in Hanoi at the end of the month (their second encounter after June 2018), and the soldier, serving as our tour guide, is wearing a green army hat instead of a helmet, underlining the stability of the current political situation.

As I watch the guard smile in unison with the sun, while taking photos with members of my group, the future seems bright for the Korean people.

Not long after, our stint at the DMZ draws to a close.

As the wintery country side passes by once more, I fall into reveries and my mind wanders off to Jo and Chang.

Will they see their dreams of reunification become a reality one day?

Will Koreans be able to cross this land freely again, in order to reconnect with their lost kin, their movement unrestricted by barbed wire and fences?

Will peace and stability return to Korea at last?

And is it even plausible to assume, that the North and South can overcome their ideological differences through diplomacy?

I wish, I had the answers. One thing seems certain though.

If unity ought to be achieved, the DMZ must vanish, not only to close the wounds of the past, but to open the path for a new chapter in Korea’s history.